Fellows Share Humanistic Perspectives on the COVID-19 Pandemic

As we look to health officials for guidance and recommendations for best practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, we are only beginning to grapple with the significant social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of this crisis.

ACLS recently reached out to a few fellows whose research has focused on public health crises past and present. They shared their thoughts on the current pandemic and how their work relates to the present moment. Their work represents a variety of perspectives, from vaccine history to racial disparities in health to responses to early plagues.

Below are excerpts from those exchanges.

Mikaëla Adams

Mikaëla Adams

Associate Professor of History at the University of Mississippi

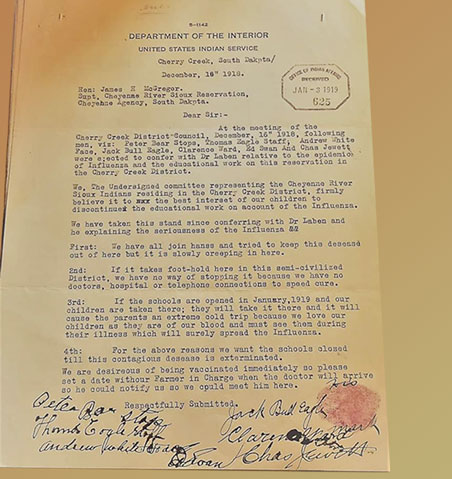

2018 ACLS Fellow: Influenza in Indian Country: Indigenous Sickness and Federal Responsibility during the 1918-1920 Pandemic

The Research

“As my research on the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic reveals, not all communities are impacted equally by deadly disease outbreaks. Indeed, Native Americans were nearly four times as likely to die from the flu as other Americans at the time. This disproportionate mortality rate reflected the economic, cultural, and racial marginalization of Native American people in the early twentieth century. Poverty, poor living conditions, racial discrimination, and insufficient federal aid left Native communities particularly vulnerable to the deadly effects of the flu, leaving them with few options during an outbreak.”

What It Can Teach Us

“Unfortunately, we are seeing a similar situation with the current crisis. COVID-19 is taking a disproportionate toll on impoverished and racially marginalized communities…Right now, the Navajo Nation in the Southwest has one of the highest COVID-19 infections rates in the country… As with the influenza pandemic of 1918-1920, the current COVID-19 crisis reflects and reveals deep inequities that continue to plague our society.”

“The influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 in Indian Country is important for what it reveals about indigenous lives and experiences in the early twentieth century, but it’s also key for understanding how governments respond to public health emergencies. By studying how indigenous people and the federal officials tasked with caring for them responded to this pandemic, we can learn about how people react under pressure and how people’s prior experiences, beliefs, and attitudes shape their decision-making in moments of crisis. Disease is not simply a biological phenomenon; it is also socially and culturally constructed. By studying disease outbreaks, we can learn a lot about a society during a specific historical moment. The same is certainly true for COVID-19.”

“The influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 in Indian Country is important for what it reveals about indigenous lives and experiences in the early twentieth century, but it’s also key for understanding how governments respond to public health emergencies. By studying how indigenous people and the federal officials tasked with caring for them responded to this pandemic, we can learn about how people react under pressure and how people’s prior experiences, beliefs, and attitudes shape their decision-making in moments of crisis. Disease is not simply a biological phenomenon; it is also socially and culturally constructed. By studying disease outbreaks, we can learn a lot about a society during a specific historical moment. The same is certainly true for COVID-19.”

- Watch this recorded lecture on “Influenza in Indian Country” by Mikaëla Adams

Anne Pollock

Anne Pollock

Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine at King’s College London

2019 ACLS Fellow: Sickening: Racism, Health Disparities, and Biopolitics in the 21st Century

The Research

“As a humanistic scholar of health and medicine, I am interested in how medical technologies and disease categories help us to tell stories about identity and difference, especially in regard to race, gender, and citizenship.”

What It Can Teach Us

“I hope that my work will help students understand our current moment, both in its exceptionalism and in its continuities. The book manuscript that I completed during my ACLS fellowship, called Sickening: Racism, Health Disparities, and Biopolitics in the 21st Century, is written with the primary audience of the undergraduate classroom in mind. The book analyzes a series of extraordinary moments that reveal fundamental racialization of access to citizenship and health in the contemporary United States: the deaths of postal workers in the 2001 anthrax attacks; the increase in chronic disease after Hurricane Katrina; the Scott sisters case, in which prison sentences were suspended conditional upon kidney donation; the differential protection of machines over people in the Flint water crisis; and so on. In the book’s conclusion, I provide a tool kit for students to analyze future events. The consequences of this crisis will impact our lives for years, and I hope that my book helps readers to make sense of them.”

Andrea Rusnock

Andrea Rusnock

Professor of History at the University of Rhode Island College of Arts and Sciences

ACLS Fellow ’13: The Birth of Vaccination: An Environmental History

The Research

“Most epidemics have been curbed by public health actions including quarantine, isolation, disinfection, and surveillance. Vaccines are relatively new to the control of infectious disease… [emerging] only in the last 150 years having played a crucial role in controlling outbreaks of numerous diseases through routine childhood vaccination since the 1960s. The race to develop vaccines during a pandemic became a feature of 20th-century biomedicine: failed efforts in the 1918-19 influenza pandemic; success with the well-funded research for polio vaccines in the 1940s and 1950s; failed efforts for HIV/AIDS vaccines since the 1980s; and limited success with vaccines for newly emerging diseases including Ebola, SARS, and MERS.”

What It Can Teach Us

“Historical research demonstrates that diseases are not just biological events; they are socially and culturally embedded experiences. Plagues and pandemics have fundamentally shaped human history: demographically, economically, politically, etc. The more we understand these histories the better our responses will be.”

Lisa Pon

Lisa Pon

Professor of Art History at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

2012 ACLS Fellow: Venice and the Early Modern Plague

The Research

“One fundamental question my project explore how could early modern Venetians ‘see’ illness or possible dangerous infectious people? They weren’t talking about microbes but marked those thought to be ill or dangerous with visible signs, that sometimes also marked innocuous individuals often of disadvantaged groups.”

What It Can Teach Us

“I am struck again by how the early modern plagues in Venice occurred during an age in which paper was the dominant media platform. How paper technologies were marshaled to help deal with the necessary bureaucracy of life and death that a pandemic requires: a postal network across the Mediterranean, paper forms with some printed information for instruction or constant data, and blanks left for contingent, future information to be filled in, paper IDs declaring the health of travelers crossing borders. We now are in a period where social media is making new ways of communication and information gathering and dissemination possible at least for some privileged parts of the global population. It is vital for our health data collection… [to] leverage the new technologies of our day.”

Gloria Kim

Gloria Kim

Assistant Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at the University of California-Riverside

2011 Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellow: The Microbial Resolve: Visualization, Mediation, Security

The Research

“The book I’m now completing on microbial life engages a wide range of issues related to this current pandemic. One of the things we are all saying about COVID-19 is that it is an event that has transformed life as we know it in the United States. But through my research, I try to say that we have, in fact, to a degree, known life this way before… One of the things I hope my book will help us to do is to ask different kinds of questions about the present.

What It Can Teach Us

“Many things are happening now that seem new and unprecedented: ‘social distancing,’ ‘flattening curves,’ stockpiling, daily measures like hand sanitizing, air-purifying, facemasks, abstaining from touch, and so forth. We’re also talking about all the ‘new normals’ of a post-COVID-19 world.

But it is important to be able to see and talk about what is and will actually be new, and to mark the changes that occur through this pandemic—while at the same time appreciating that this is not a radical historical departure, and are part of a longer historical project developed in and through microbes. My research shows that these ‘new’ responses are actually part of a much longer historical project developed in and through microbes.” When charted historically we can more effectively identify and work on points of political intervention such as the current administration. Still, what we are experiencing now is rooted beyond this administration and long precede it. There is a deeper, slower story about certain states, above all the US, and their ideological and material commitments to making militarization, capitalism, and colonialism platforms of world-making.

- Read Gloria Kim’s essay in Project MUSE for more on her research.

Ruth MacKay

Ruth MacKay

Independent Scholar

2015 ACLS Fellow: Life in a Time of Pestilence

The Research

“I am a scholar of early modern Spanish political and social history. I titled my book Life in a Time of Pestilence because I was interested in how structures, customs, and relationships somehow survived amid all the death and destruction of plague. I chose plague as a topic not because I expected it to be relevant but because I knew it would embrace a wide range of problems. Bubonic plague came and went in Spain on multiple occasions, but the worst visitation was probably in 1596-1601. I looked at towns and cities in the upper half of the Iberian Peninsula, mostly using municipal documents, in an effort to understand quarantine, daily life, judicial and political structures, economic relations, disease, and death. I discovered ingenuity, bravery, charity, common sense, patience, and lies.”

What It Can Teach Us

“There are many parallels with the situation today. I can offer three examples: First, the methods that late-16th-century Spaniards used to figure out causes and effects were mostly based on inductive reasoning. Authorities relied upon medical professionals but were guided by the same logical methods they (and we) used in law and politics. Second, negotiations between authorities and commoners to balance the competing requirements of economic survival and public health were frequent, as townspeople begged to be allowed access to fields or to hold open markets. And third, they were sick of quarantine. But, unlike today’s anti-quarantine protesters, they did not argue in terms of “freedom,” but rather simply of survival.”