- Lean on the resources offered by your scholarly association. Take advantage of any opportunity you have to learn from others in your field facing similar challenges.

- Get as many faculty members invested in the project as possible. When the initial point person steps away, the project will need to be taken up by other people who believe in it and will do different things with it.

- Working with a client to set a research agenda is good professional development for students, and it can circumvent the impulse to only take courses that deepen students’ knowledge of their subfield.

- Creating opportunities for teaching these sorts of classes can reinvigorate faculty teaching and engagement.

University of Michigan HistoryLabs

In 2017, the American Historical Association (AHA) was running the second wave of its Career Diversity Initiative. Rita Chin from ACLS Consortium Member the University of Michigan was director of graduate studies in the history department. Faculty members had seen the latest numbers for the academic job market and realized that the situation was not improving. Department leaders believed it was important to take action but did not feel well-equipped. They decided to leverage the resources of their scholarly association. In her role as DGS, Chin applied and was accepted to the AHA’s Career Diversity Faculty Institute in Chicago, an event designed to help faculty learn how to support their PhD students in exploring different career pathways and opportunities.

In attending the AHA’s institute, Chin realized that the history department was operating under traditional definitions of success focused on faculty positions and that those definitions of success needed to be expanded to include paths and positions beyond the academy. Students who earned their PhDs and went on to other kinds of employment could and should also be considered successful. Chin returned to Michigan and began thinking with faculty colleagues about “low-hanging fruit”––that is, smaller changes and tweaks that could be made to allow students to engage in career exploration. Although faculty were concerned that they wouldn’t know how to give students concrete ideas about how to do this sort of career exploration, they were willing to start by changing some of the assignments in their classes, such as asking students to produce different types of writing for different audiences.

A number of faculty experimented with these modest changes, but some were more ambitious. They quickly zeroed in on collaboration, identified by the AHA as one of five core competencies important to historians working outside the academy, often unfamiliar to practitioners of a discipline rooted in solitary research and writing. The faculty began asking how they could teach collaboration, considering that academic historians rarely collaborate themselves. The idea of working with clients, which had been raised at the AHA institute, became a way to imagine redesigning the research seminar. Working on a research agenda set by a client, Chin says, prevented graduate students from having to agree on a single collaborative project. The emphasis placed on individual interests and subfield expertise in graduate school makes that sort of collaboration difficult. But if the client decided the research agenda, then everyone could work together on a single, common project. They called these projects HistoryLabs.

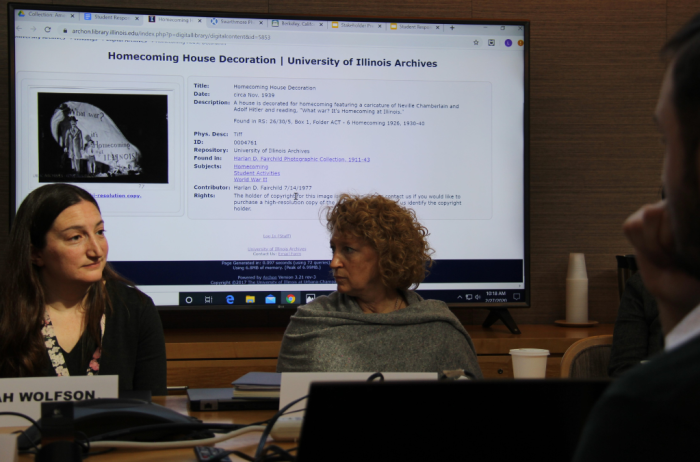

The first HistoryLab course in the winter of 2019 was a collaboration with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). The museum had created a teaching website called Experiencing History, which hosted tools for college-level teaching of the Holocaust. The museum asked the Michigan graduate students to develop new collections of primary sources based on themes such as “American Knowledge of Fascism.” Students worked as a team to explore primary sources and together chose 15 to include in their collection; they then collectively wrote and edited all of the descriptions and analysis that would accompany the sources on the Experiencing History website.

Students learn to articulate what they did in terms of transferable skills––and faculty learn how to help them. The labs also help students become more aware of what they’ve learned and their own capabilities, and they increase their confidence in their ability to use what they’ve learned in different ways.

Since then, there have been several other history labs that have run (including a second, COVID-disrupted iteration of the USHMM course in winter of 2020). The AHA itself served as a client for one lab, which investigated its institutional history in relation to race and discrimination. A lab in conjunction with the Detroit Institute of Arts asked students to create a virtual field trip for the city’s Diego Rivera murals. The most recent, and possibly most complicated, iteration of the lab was a joint effort between Chin and Earl Lewis, professor of history and the founding director of the Center for Social Solutions at Michigan and the Crafting Democratic Futures Project. Lewis and Chin’s HistoryLab had three clients, each with a team of students:

- WQED, a local PBS affiliate, was filming a documentary of the entire Creating Democratic Futures project. Michigan graduate students researched global cases of reparations to help the filmmakers contextualize the American case in a broader global set of debates about reparations. Students also prepared supplementary materials for the PBS website. The documentary, The Cost of Inheritance, premiered in January 2024.

- A race and equity officer of Washtenaw County, where the University of Michigan is located, asked students to investigate how reparations work at the community level and to collect information on any city-, county-, or state-level reparations that had been implemented in the US. This officer requested a policy paper about the infrastructure that was created for each reparations effort, in preparation for starting a county-level, community-based reparations initiative.

- A community partner in Detroit wanted to understand what had been lost in the building of a highway through a Black neighborhood in the 1960s. The student team created a database and documented every building that was destroyed on the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare, including which ones were businesses and which ones were residences. In doing so, they discovered that a majority of the street’s residents had not owned their property, which made it difficult to quantify the loss in a traditional manner.

Chin has now taught three HistoryLab courses. She says they broaden the horizons of the students who participate and provide a number of metacognitive benefits. Students learn to articulate what they did in terms of transferable skills––and faculty learn how to help them. The labs also help students become more aware of what they’ve learned and their own capabilities, and they increase their confidence in their ability to use what they’ve learned in different ways. Anecdotally, former students have benefited professionally from their experiences in the labs––and this is true not only for students who went on to positions outside the academy, but also for students who became faculty members.

The current HistoryLab, as of spring 2024, is focused on the history of the University of Michigan in relation to Native land acquisition as part of the university’s Inclusive History Project. The future of the program is somewhat unclear. COVID was extremely disruptive, as it not only made working in person impossible, it also sapped faculty members of their energy. However, Chin underscored how much fun teaching a lab is. “HistoryLabs can be a place of exploration not only for students learning to collaborate,” she says, “but also for faculty who want to try something new and do something different.”